By Shelby Gallien

Photos by Jeff Jaeger

Originally published in the July 2016 Issue of Muzzle Blasts Magazine. Subscribe today to access the entire back catalog of Muzzle Blasts digitally from your home.

Figure l: This classic Washington Hatfield rifle demonstrates most of the distinctive details found in his work. Hatfield rifles are usually fully-stocked in straight-grained walnut with a forged iron butt plate and trigger guard. The distinctive guard has a “U” shaped bow with a large reverse curl rear spur. Side facings are tight, slightly pointed at front and rear, with an even margin of wood around the lock plate. The entry ramrod pipe has no flange and buts up against a flat area in Tennessee style: a brass strip reinforces the forestock around the entry pipe hole. Private collection; photo by J. Jaeger

Foreword:

George Washington Hatfield made distinctive rifles in soud1ern Indiana from about 183 I until after the Civil War; his work shows the influences of his early training in Fentress County, Tennessee. Despite substantial infom1ation surviving 011 Hatfield himself; only a handful of his rifles were known. This two-part article will re-examine the work of Hatfield in light of two recent discoveries.

In 2003 the author published a substantial two-part article titled "Washington Hatfield: Indiana's Gunsmithing Legend" in the September and October issues of Muzzle Blasts magazine, The article provided a detailed biography of Hatfield in "Part I" followed by a review of his known work in "Part fl." Back in 2003 the known Hatfield rifles were generally well-made but lacked any significant decoration. They had long barrels fully-stocked in walnut, iron guards with large reverse-curl rear spurs, and Hatfield's "trademark" cast pewter chevron-style nose caps. A good example of Hatfield's work is shown in figure L. His guns were made for the common man rather than the wealthier gentlemen of the day who demanded finer arms.

More recently two outstanding Hatfield 1ifles have been discovered that show a new dimension of his work. They are finer and more extensively decorated than any previously known Hatfield rifle, and therefore require us to reassess his artistic skills as a gunsmith. This article examines the new rifles and their impact on what we know or thought we knew, about Washington Hatfield as a gunsmith during Indiana's settlement days. Three additional unpublished Hartfield rifles are also examined for their contributions to our knowledge of Hatfield's work. While not as heavily decorated as the first two rifles, each provides fresh insights into the breadth of Hatfield's work and helps build a more complete understanding of his true abilities as one of Indian's most interesting frontier gunsmiths.

Hatfield’s Working Life:

George Washington Hatfield was born to parents Ale Hatfield and his second wife. Elizabeth Young, on January 13, 1813, in Anderson County, Tennessee. From early childhood, he was called Washington, or "Wash" for short. ln 1820 the family moved to Wayne County, Kentucky, where Washington learned to use a rifle and hunt deer and bear from his older brother Emmanuel. During the mid-1820s the family moved again, going south across the state line to Fentress County, Tennessee. Fentress County was where

Washington learned the gunsmith's trade, but his training ended prematurely in 1831 when the family moved to Greene County, Indiana. There they built new homes in the wilderness where ''there was not a single cabin but my father's for many miles around," according to brother Emmanuel in later years. Washington briefly lived with his parents in Indiana, but in March of 1832 be married Elizabeth Snyder of Greene County and purchased eighty acres of land about three miles from the cabins of his father and brother Emanuel. There he built a house, barn, and a gun shop along the trail/road in front of his property. He lived on this homestead for the rest of his life, working as a gunsmith, farrier, blacksmith, and farmer. When he died in 1884, Iii'; family fulfilled his request to be buried on top of the hill behind his house He rests here today in a single marked grave.

Figure 2: Washington Hatfield signed his guns with his initials “W H” in large block letters. The initials wewre usually placed on the barrel or a cheekpiece inlay. Note the initials were usually formed with straight lines with balls at the ends; both lines and balls appear to be punched into the metal rather than engraved. This signature example comes from the well decorated rifle in figure 4. Courtesy J Jaeger; photo by J Jaeger

Washington Hatfield began working as a gunsmith in 1832 in Greene County. The author has seen about a dozen Hatfield rifles: half were signed and the others attributed based on the many distinctive details Hatfield used in his work A hunting knife marked with Hatfield's distinctive "W. H:· signature have also survived. All known guns are percussion ignition despite Hatfield having worked early enough to make flintlock rifle during his first years. Perhaps his back-woods location resulted in mostly repair work during his first years, until the local population and Economy grew sufficiently strong to support the demand for new rifles. In true backwoods fashion, Hatfield also worked at several trades associated with gunsmithing: blacksmithing, mechanics work, and farrier’s work. With uncertain demand on the frontier, a more widely skilled craftsman had a better chance of success. There is no record of how long Hatfield made guns in Indiana If one assumes a healthy gunsmith would work into his mid-sixties, then Hatfield probably built guns well into the 1870s.

Figure 3a: This is one of Hatfield finest known rifles. Stock wood is vivid curly maple rather than the usual walnut, and many small german silver inlays are present. The rifle has Hatfield’s typical iron guard with a “U” shaped bow and a large, sweeping rear spur coming off the grip rail. The large arrow inlay, used on other Hatfield rifles, was always placed where a capbox would have been located. Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company, Rock Island, IL. Photo by R. Burkeybile

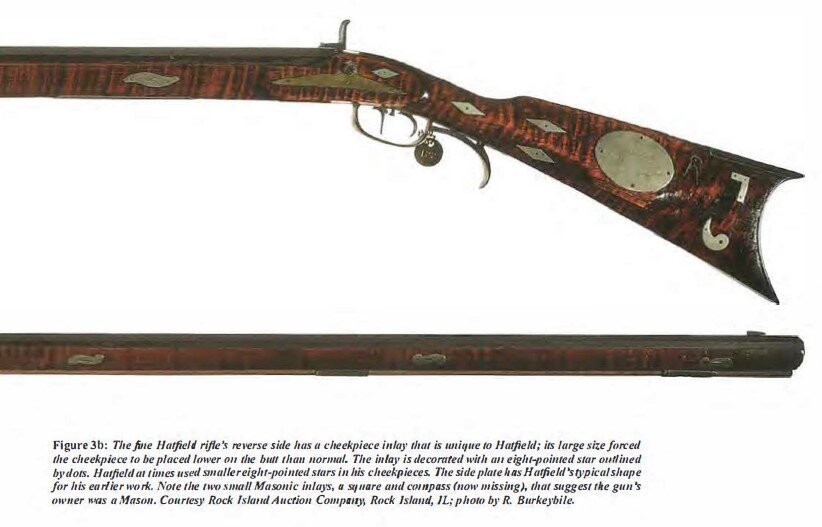

Figure 3b: The fine Hatfield rifle’s reverse side has a cheekpiece inlay that is unique to Hatfield; it’s large size forced the cheekpiece to be placed lower on the butt than normal. The inlay is decorated with an eight pointed star outlined by dots. Hatfield at times used smaller eight pointed stars in his cheek pieces. The side plate has Hatfield’s typical shape for his earlier work. Note the two small Masonic inlays, a square and compass (now missing), that suggest the gun’s owner was a Mason. Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company, Rock Island, IL; photo by R. Burkeybile

First Decorated Rifle

One of the earliest and finest known Hatfield rifles is illustrated in Figure 3A. While unsigned, it is easily attributed to Hatfield based on its distinctive trigger guard, stock architecture, side facings, side plate, and the use of many small diamond-shaped inlays. Early details include: larger than normal side plate, tall butt with a less pointed toe than on later rifles; large oval cheekpiece inlay; large rear spur on guard; and heavier use of inlays than on later rifles. These details can be seen in figure 3b. The gun is stocked in fine curly maple and has typical Hatfield mixed-metal furniture with the large guard and butt plate being made of forged iron while the smaller ramrod pipes and nose caps are sheet brass. There are twenty-eight German silver inlays on the gun counting the small wear plate under the forestock grip area, a huge number for a Hatfield rifle. It should be noted that Hatfield did not engrave the inlays. Even his initial signature “W H” found on many of his guns is not engraved; it appears to be made by punching both the straight lines that form the letters and the small dots that decorate the letters’ tips as seen in figure 2. His lack of engraving may have been due to his shortened training period in Fentress County, Tennessee which ended prematurely in 1831 when Washington was only eighteen and a half years old. He probably learned the basic skills of gun building, but not the decorative skills of engraving that would have been taught near the end of an apprenticeship period after construction skills were mastered.

The rifles forestock inlays are not Hatfields standard oval or diamond-shaped inlays. Rather, they are unique for a Hatfield rifle with their slightly “S” curved outline. Additional details of the gun are shown in Figure 3c. The rifle probably dates to the mid-1830s and is one of the most heavily decorated Hatfield rifles yet seen. The gun has conventional brass ramrod pipes with the expected decorative ring filed at either end. Later Hatfield rifles had more distinctive ramrod pipes, at times made of copper, with pronounced raised area at either end; these pipes are sometimes referred to as “plumbing fittings” due to their odd appearance. A 41 ⅝” barrel gives the rifle a slender, elegant appearance. Fine architecture, great stock wood, and multiple inlays make it one of Hatfield’s finest rifles. The gun demonstrates an artistic sensibility well beyond Hatfield’s usual walnut stocked, iron mounted rifles with minimal decoration; it elevates Hatfield’s reputation from that of a good maker of basic rifles, to someone who could rise to the occasion when a fine rifle was demanded by a more discerning customer.

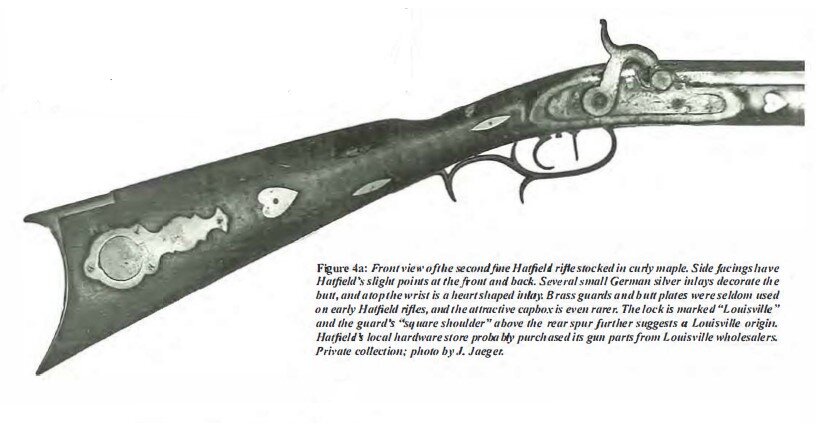

Figure 4a: Front view of the second fine Hatfield rifle stocked in curly maple. Side facings have Hatfield’s slight points at the front and back. Several small German silver inlays decorate the butt, and atop the wrist is the heart shaped inlay. Brass guards and butt plates were seldom used on early Hatfield rifles, and the attractive capbox is even rarer. The lock is marked “Louisville” and the guard’s “square shoulder” above the rear spur further suggests a Louisville origin. Hatfield’s local hardware store probably purchased its gun parts from Louisville wholesalers. Private collection; photo by J. Jaeger.

Second Decorated Rifle

Another Hatfield rifle of exceptional quality is shown in figure 4a. The gun is fully-stocked in curly maple and to-date is the only known Hatfield rifle with a cap box in the butt. The gun is tastefully decorated with many small Geman silver inlays, including ovals around the butt and along the fore-stock at the bane! pin locations. Several small hearts are present in addition to a cheekpiece star and a moon inlay behind the cheek. Stock architecture is slim and graceful, and all mountings are brass suggesting an earlier Hatfield rifle. The butt plate and trigger guard appear to be commercial items. The lock plate is marked ''Louisville,'' and the guard has a Louisville style "square shoulder" above the rear spur where it extends up to meet the guard's rear extension. The guard and lock are shown in figure 4b. Hatfield may have gone to Louisville to purchase gunsmithing supplies, or perhaps a Greene County hardware store stocked gun parts acquired from Louisville wholesalers. Close inspection of the lock shows it to be a late flintlock converted to percussion. The lock is attached by a single bolt bur has a plugged From bolt hole. The gun could have been made as a late, single bolt flintlock, but it is more likely that an older lock was modernized to percussion for this particular rifle. The rifle's single lock bolt can be seen in figure 4c. The rifle probably dates to the late 1830s, making it a little later than the first illustrated rifle. Dating is based in part on the rifle's butt having slightly less height, a more extended toe, and the presence of barrel pins rather than wedges.

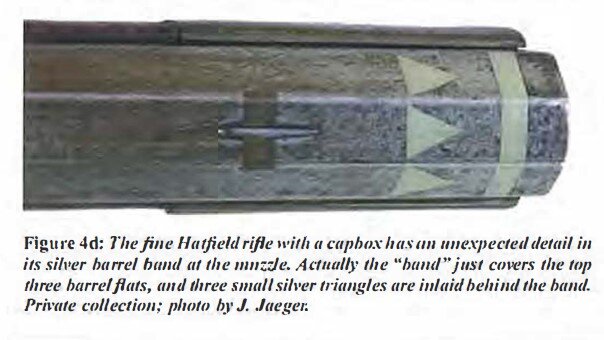

An important detail on the second rifle is Hatfield's signature comprised of his initials "W • H" in large block letters on a silver barrel inlay; the signature is shown in prior figure 2. Due to the rifle's use of conventional brass furniture for its guard, butt plate, nose cap, and ramrod pipes, the signature is important to verify the item was actually made by Hatfield since most of his rifles have iron guards and butt plates along with his trademark cast pewter chevron-style nose caps and walnut stocks. The gun carries twenty-five inlays that include a silver barrel band just behind the muzzle with three smaller silver triangles behind the band; the unique muzzle decoration is shown in figure 4d. The inlaid muzzle detail is perhaps reminiscent of the several "teeth" or triangular points at the rear of his preferred cast pewter chevron style nose caps. Despite the surprising amount of inlay work, unexpected muzzle decoration, and conventional brass furniture, the gun retains many standard Hatfield features. The stock architecture, side facings, cheekpiece position and shape, cheekpiece inlay, and lock bolt washer are all purely Hatfield in design.

Significance of the Two Decorated Hatfield Rifles:

Figure 4b: The reverse of the second fine Hatfield Rifle shows its simple but attractive inlay work. The cheek is decorated with Hatfield’s standard eight-pointed star, and the smaller side plate is also typical of his work. A crescent moon inlay behind the cheepiece may have been influenced by large moons inlaid in the same area on some early central Kentucky rifles. The cheeppiece is a good example of Hatfield’s work, being relativly small, low on the butt, with a single heavy incised line across its base. Private collection; Photo by J. Jaeger

The two well-decorated George Washington Hatfield rifles are important discoveries. Until their appearance, all known Hatfield guns were fully-stocked in walnut with minimal decoration. Earlier pieces had forged iron butt plates and guards with brass or copper ramrod pipes. Side plates (if large) or lock bolt washers (if small) were either iron or brass and the distinctive Hatfield nose cap was cast pewter in a chevron design. A few inlays were used, most notably on Hatfield's personal rifle that has survived and is on display at the Bedford County, Indiana, Historical Museum. Several late guns are known with commercial brass butt plates and guards; by the time they were made, it was probably cheaper for Hatfield to purchase parts than forge them. All previously known guns were well made with slim lines and good stock architecture, but all were relatively plain. Patch boxes and cap boxes were unknown on Hatfield rifles, inlays seldom used, and curly maple stock wood almost never seen. Hatfield's abilities were presumed to be those of a good craftsman but not an artist who knew how to decorate his products when customers wanted something better. The discovery of the two highly inlaid rifles with attractive curly maple stocks has changed our perception of Hatfield as a gunsmith. We now know he was capable of greater artistic expression than previously thought, and in fact, could make attractive, well-decorated rifles when tile demand presented itself But while he could enhance a rifle's appearance with good inlay work, he was reluctant to engrave his metal surfaces or use molding lines to further enhance his guns ... probably the result of his shortened training/apprenticeship period.